Guest Post by Antonio R. Gargiulo, MD

Guest Post by Antonio R. Gargiulo, MD

Endometriosis used to be an obscure diagnosis, often eluding medical providers for years and puzzling patients when we broke the news to them following laparoscopic surgery. Today I would argue that endometriosis has become a household medical term. This is thanks to a relentless patient-led information campaign that has sensitized the medical community and has created widespread social awareness over the past few years. Most women who currently seek advice for infertility or chronic pelvic pain have some idea about endometriosis.

For those that have managed to miss the plethora of available information online about endometriosis, a brief introduction will be helpful here. Endometriosis is a common condition that consists of nodular inflammatory growths found on or about the pelvic organs (albeit any abdominal organ and even extra-abdominal organs may be affected). This condition can be asymptomatic, but in many cases can lead to disease: mainly, to infertility and pelvic pain. Endometriosis remains a biological mystery, because we do not yet fully understand what causes it. It is commonly said that it is due to growth of the uterine lining (endometrium) outside of the uterine cavity (aka: the endometrial cavity), because that’s what endo looks like under a microscope. But of course, if endometriosis were simply a self-transplant (i.e. a tissue changing its location within our body), it would not cause inflammation, which is a central feature of the condition. This simple consideration shows just how much we do not yet understand about endometriosis. Endometriosis cannot be cured, but it can almost always be successfully treated by highly specialized centers, with a combination of medical, surgical, and physical therapy.

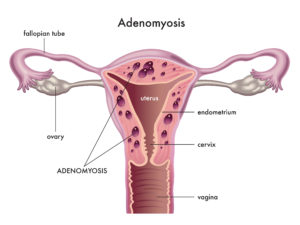

Now that we are all on the same page regarding endometriosis, let’s talk about an even more obscure condition, which is endometriosis-related and becoming more frequently diagnosed lately. It is adenomyosis, which means “endometriosis of the uterine muscle.” Endometriosis that strikes at the uterus itself is obviously threatening the very core of the reproductive process. Adenomyosis, in its most severe manifestations, can result in absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). And this is just one of the many reasons why some consider adenomyosis “the ugly cousin of endometriosis”. Hysterectomy is very rarely recommended for endometriosis, but adenomyosis can cause such severe menstrual bleeding and pain that hysterectomy is sometimes indicated, even before a woman has completed childbearing. Unfortunately, even in the absence of symptoms that lead to hysterectomy, adenomyosis is perfectly capable of making the uterus unsuitable to sustain a pregnancy. To add insult to injury, adenomyosis tends to disproportionately impact women of advanced reproductive age, who already face formidable challenges in their endeavor to start or grow their family. Finally, adenomyosis’ negative impact on embryo implantation is highest in obese women, with a compounded effect that greatly reduces IVF success, even when chromosomally normal embryos are selected for transfer. To underline how much this condition is still poorly understood, I should say that at this point there is no official classification of adenomyosis, and no standardized recommendations for medical or surgical treatments exist. Unfortunately, as with endometriosis, there is no cure for adenomyosis.

When I was a reproductive endocrinologist in training, a generation ago, adenomyosis was diagnosed almost exclusively AFTER hysterectomy. Hence, it rarely presented as a therapeutic dilemma in infertile patients. This has changed drastically with technological improvements in radiological imaging. Remember the old VHS tapes and TV sets of the 90s? Our ultrasound and MRI machines were not too far ahead of those in terms of resolution and detail, at that time. Progress in video and computer technology has since continued exponentially, and we have progressively become able to “see” pathology that had been hidden to ultrasound and MRI for decades. As a result, in this age of technological transition, patients are exposed to the double trouble of underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis. The trouble of underdiagnosis is obviously facing an unknown, smoldering, condition that can – at a very minimum – cost precious time and financial expenditure for the patient. The trouble of overdiagnosis is, conversely, that of steering fertility and gynecologic treatment towards untimely, radical treatment choices.

In conclusion, adenomyosis is a very serious form of endometriosis that affects the uterine wall. Even though its manifestations are not currently classified in a standard fashion, we now understand that adenomyosis comes in many forms and many degrees. We will eventually better understand how adenomyosis can and should be treated, and what types and degrees of adenomyosis preclude reasonable chances of successful pregnancy. At this point in time, however, patients facing infertility should become familiar with some key concepts that may assist them in dealing with this challenging diagnosis.

Here are my top ten considerations for an infertility patient diagnosed with adenomyosis:

1) As opposed to endometriosis, adenomyosis is NOT a surgical diagnosis. Biopsy is likewise not needed, as radiologic imaging is just as predictive.

2) There is no “sure” radiologic diagnosis of adenomyosis: however, highly specialized centers claim a 98% accuracy for both ultrasound and MRI. In non-specialized centers, false negatives and false positives are common.

3) There is no blood test that can diagnose adenomyosis.

4) Hysterectomy for severe adenomyosis is sometimes necessary, even before the completion of childbearing, for patients who do not have success with other forms of medical treatment.

5) Gestational surrogacy has been successfully used for decades to help women with adenomyosis have their own biological children. This option is legal in most states in America (including all of the New England states) but is illegal in many nations worldwide. It can be ethically and financially challenging.

6) Uterine transplantation, an experimental treatment option introduced in 2014, has already produced over 30 healthy children in women lacking a uterus, and will eventually become a more widely accessible treatment modality for patients with severe adenomyosis needing a hysterectomy.

7) Adenomyosis infiltrates the uterine wall, as opposed to uterine fibroids, that displace (and spare) the surrounding tissue. Consequently, surgical removal of adenomyosis removes part of the uterine wall. Surgery for adenomyosis can therefore be considered a “partial hysterectomy,” in that a certain part of the uterine wall is irreversibly lost. Whenever a conservative surgery for adenomyosis is recommended in a woman that has not completed childbearing, a second, and even a third, surgical opinions should always be sought, with no exceptions.

8) Adenomyosis can disguise as a uterine fibroid when ultrasound is the only imaging modality employed. When excision surgery for uterine fibroids (myomectomy) is planned, patients should demand an MRI (unless the surgery is hysteroscopic).

9) Adenomyosis is one of the few endometriosis-related scenarios in which the prolonged use of GnRH agonists and antagonists may be justified, as a “lesser evil” option in the setting of assisted reproductive technology treatments.

10) Try not to despair if adenomyosis is brought up in your consultation. There is still so much that we doctors do not understand about this condition, but we know that its spectrum is vast and that many patients do well without any intervention.

Ultimately, adenomyosis is a very complex uterine anomaly. It falls squarely outside of the field of expertise of general gynecologists and family physicians. Very few specialists are currently able to adequately diagnose and manage this condition. I recommend that you consult primarily with your reproductive endocrinologist and inquire about the availability of a second opinion with a reproductive surgeon in your area.

Antonio Gargiulo, MD is the Medical Director of Robotic Surgery, as well as reproductive endocrinologist and surgeon in the Center for Infertility and Reproductive Surgery (CIRS) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts and the Medical Director of the Center for Reproductive Care and Medical Director of Robotic Surgery at Exeter Hospital in New Hampshire. Dr. Gargiulo is an Associate Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology at Harvard Medical School.